Diego considers himself fortunate.

The 49-year-old man, who is only being identified by his first name for privacy reasons, thinks back on some dark moments in his life —all associated with drugs.

He said his brothers introduced him to narcotics when he was 12 and living in his hometown of Springfield, Massachusetts. By the time he was 17, said Diego, who is of Puerto Rican descent, he was not only using drugs, but also trafficking in them. He said the drugs plunged him into a spiral of addiction, fracturing his family relationships and landing him in jail numerous times.

But at least the drugs didn’t kill him, he said with relief during a phone interview.

“I think I am lucky. I lost a nephew in December 2020. I lost two of my four brothers, one in 2008 and one in 2018. All from overdoses,” he said. “But I don’t have to be my brothers or my nephew.”

Diego spoke to Noticias Telemundo from Casa Esperanza, a Boston-based behavioral health facility and one of the few U.S. centers that offer detoxification and mental health services in Spanish.

The federal government’s Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, or SAMHSA, described the issue of uncontrolled opioid use in the Latino community as a “matter of urgency” in a special report released in 2020.

With the coronavirus pandemic — and the confinement, depression and financial stress that it has caused — opioid use in the country has skyrocketed, studies have found. Overdose deaths have increased by a historic 16.9 percent nationally, according to a recent report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It cited more than 81,000 deaths in the 12 months ending in May 2020 — the highest number of overdose deaths in a 12-month period in U.S. history and one of the factors that led to a one-year reduction in life expectancy in the country, something that has not happened so dramatically since World War II.

The CDC does not yet have complete data on overdose deaths in the months after May 2020, but since the pandemic is ongoing, experts fear the death toll from opioid abuse during the global health emergency will be much higher.

Some states have seen a troubling rise in cases among Latinos.

Rising Latino deaths

In Maryland, the Opioid Operational Command Center reported that from January to September 2020, deaths related to opioid use increased by 16 percent among non-Hispanic whites and 13 percent among non-Hispanic Blacks — while Latinos saw an increase of 27.3 percent.

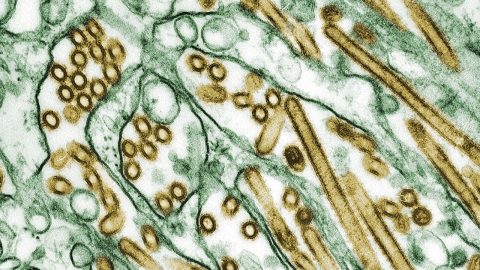

There is no complete data yet on which drugs caused the most overdose deaths in 2020, but fentanyl and methamphetamine (or a mixture of the two) appear to have been the most common narcotics behind deaths last year. This may be in response to the fact that heroin imports were affected by the pandemic, while the other two opioids have continued to circulate as usual within the country.

“We Hispanics are the ones who are dying,” Diego said. At times, he finds it hard to believe that he was able to enter a recovery program like that of Casa Esperanza, where the demand is high and is growing.

“The cases we are getting during the pandemic have been very high, double [the usual],” said Orlando Colón, 55, who directs Casa Esperanza’s residential recovery program for men, offering six to nine months of treatment to patients in need of sustained care.

“Unfortunately, we are now full. When one of the 50 beds we have is emptied, we call the next one on the list,” he said. Those who are not able to enroll and cannot afford separate housing end up in shelters or on the street, where it is common for them to continue using drugs.

Colón said it’s even more difficult for immigrants, especially those who lack legal status, who are sometimes too afraid to get help. The inability to access the necessary help in a timely manner contributes to aggravating addiction problems and increases the chances of death from overdoses.

Effects multiply for the most vulnerable

The coronavirus outbreak has hit people suffering from addictions in numerous ways, Colón said.

“Many have asked relatives for help, but family members are afraid to open their doors because of the pandemic,” he said. In-person counseling services have been affected by group meeting restrictions. “Before, there was direct counseling, but now a lot of this is on Zoom and it becomes more difficult.”

Before entering the recovery program, Diego said, he had served prison time for a drug-related case. He said those with mental health issues in prison suffered because of the pandemic; weekly sessions with a specialist, for example, were stopped except for emergencies.

“They also took away all study and work programs, and visits,” Diego said. People suffering from addiction who have been released from jail and don’t have a cellphone or a computer are having a tougher time accessing digital platforms to receive lifesaving help.

Colón, who has worked at the center for 14 years, said depression and economic stress contribute to issues of addiction. Among immigrants, the trauma of migration, the fear of deportation and the lack of an extended family network are added factors.

Latino adults have experienced more depression and suicidal thoughts than other groups during the pandemic, according to a CDC report published in February.

Stress over basic needs

Latinos surveyed reported a “higher prevalence of psychosocial stress related to not having enough food or stable housing than did adults in other racial and ethnic groups,” according to the CDC, as the pandemic affects so many Hispanic families and workers.

Symptoms of depression were reported 59 percent more frequently by Latino adults (40.3 percent) than by non-Hispanic whites, (25.3 percent), according to the report. Nearly 37 percent of Hispanics who were surveyed reported an increase in substance use or reported they had started to use, compared to below 16 percent for whites and Blacks.

“In public health, what we see most often is that when economic problems worsen, when people are out of work and there’s too much stress — something that got worse for Latinos with the pandemic — that obviously increases the use of alcohol and drugs,” Dr. Lisa Fortuna, head of the department of psychiatry at San Francisco General Hospital, told Noticias Telemundo.

“For those who already had drug problems, relapses increased because people try to cope with stress. This has created even more problems because it has brought more depression, emotional difficulties and even physical illnesses,” she said.

The stigma persists

In her experience treating Latino patients with depression, anxiety and addiction problems, Fortuna said that a stigma persists around seeking help, and that lack of help often leads to the consumption and abuse of substances.

“Many do not publicly acknowledge that they suffer from depression or anxiety, for fear of being called crazy or weak, and they acknowledge even less that they are consuming alcohol or drugs,” she said.

Sometimes, she said, Latinos will seek help through religious institutions instead of seeking professional help. But she warns that while studies say that having faith or following a religion can make people less susceptible to becoming depressed or thinking about suicide, “this is not a complete prevention against depression.”

Before the coronavirus hit, the U.S. was already suffering from the deadliest opioid overdose epidemic in its history. The overdose death rate among the national population has been increasing dramatically in recent years.

In 2019, 71,000 Americans died from substance abuse, and the country declared overdose deaths a national public health emergency.

By the late 1990s, the increase in overdose deaths was linked to the abuse of prescription analgesic opioids, such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, codeine, morphine and others.

In the 2000s, cheaper and deadlier illegal drugs such as heroin and fentanyl gained ground. By 2015, heroin had caused more deaths than prescription painkillers or other drugs. And in 2016, fentanyl and other similar pills claimed the most lives.

About 4 percent of the U.S. Latino population abuses opioids, and this includes people as young as 12, according to SAMHSA.

Fortuna said many doctors across the country are urging a reform of the primary health system so that patients who go for a physical checkup can get mental health counseling right there. She thinks this would make a difference among those who wouldn’t voluntarily go to a mental health practitioner.

“There’s a movement in the U.S. to integrate the two things, mental health and physical health. In fact, it’s already happening in a lot of clinics at the federal level,” she says.

Amid challenges, “I see a good future”

SAMHSA warns in its 2020 report that bilingual behavioral health professionals are in high demand because of their small numbers. This shortage remains an important barrier to offering prevention, treatment and recovery programs for many Latinos.

Casa Esperanza’s Colón said it’s a challenge to keep someone off drugs. Many of those who use their services end up relapsing or dying of overdoses.

“If 10 clients complete the program and leave, eight of them come back looking for the service again,” he said. That’s in the best of cases, since many die from overdoses.

Others manage to get out of the black hole of addiction and get their life back. Many of them have even ended up working at Casa Esperanza, where they were once patients. “Of our 11 recovery experts, eight used to be clients. That they want to stay working with us makes us proud because it makes us think that we did things well,” Colón said.

Diego hopes to work as a mechanic when he finishes his recovery. He wants to visit schools and tell teens to avoid the life he started at their age.

“I see a good future for me. Many of the counselors here went through this program and that gives me hope that it can be done,” he said. “I have to work on my recovery, deal with my addiction. That is the primary thing is my life. I know that in this program, they are going to help me a lot. They are already doing it.”

An earlier version of this article was originally published in Noticias Telemundo.

Follow NBC Latino on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Recent Comments