The staff of El Centro de Corazón health clinics knew that Covid-19’s strike would be more vicious in Houston’s East End, where many Latinos live on the economic edge.

When the first of the clinics’ employees reported symptoms in early 2020, the staff wept, said Dr. Kavon Young, medical director of El Centro’s four clinics.

They wept for their colleague and “they wept not only for themselves, but for their family members that were living in their houses,” Young said. “That was a huge moment for us, because the pandemic had finally hit home.”

Many of the more than 100 employees of El Centro de Corazón were as vulnerable as the patients who would come in, contending with the same challenges as their clients, like staff members at other community clinics in the U.S.

They live in the clinics’ neighborhoods, in small homes or single-bedroom apartments, sometimes sharing with multiple family members.

They have unreliable or no transportation, higher incidences of certain diseases and limited health care options. They don’t all have broadband access at home and some grapple with language barriers.

Across the country, Latino clinics like El Centro de Corazón, a Federally Qualified Health Center, have acted as levees against the coronavirus, which has threatened from the start to devastate their communities.

Early on in the pandemic, they knew they would have to find their own ways to inform their communities about the virus and treat them when they got sick, at the same time cutting through patients’ fears of medical costs or of the government — ensuring that their populations weren’t forgotten.

As the country has moved to massive vaccination hubs and online vaccination appointment systems, some Latino health clinics are calling on federal and state governments to use them more to reach vulnerable communities, in particular people of color and immigrant populations, and to stock them with resources to do so.

“Community health centers are perfect for these times, because we have been looking at the social determinants of health well before the pandemic,” Young said.

The need to step up vaccinations while still trying to stop the spread of Covid-19 makes the clinics’ role even more relevant.

Of the slightly more than half of the 62.5 million people who have received at least one vaccine dose, 65.5 percent were white, compared to just 8.5 percent who were Latino, according to demographic data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Frankie Miranda, president and CEO of the Hispanic Federation, said African Americans have been successful in using black churches for vaccinations but Latinos are less successful because the most vulnerable in the community are undocumented.

“We’re a trusted source in our communities,” said Dr. Viju Jacob, an assistant vice president for Urban Health Plan, a network of health centers in New York that serve 90,000 predominantly Latino patients in the South Bronx, Central Harlem, Corona and Queens.

Urban Health Plan is one of the largest employers in many of the ZIP codes where it has clinics, “so that in itself has a built-in level of trust. Our employees essentially represent the community,” Jacob said.

El Centro de Corazón, Urban Health Plan and other similar clinics are generally nonprofits that charge on a sliding scale or not at all and take patients on Medicaid or Medicare.

More Covid services — and a need for more funding

Many of the clinics have scrambled to find outside funding to buy and install partitions and other equipment to continue serving patients safely, as well money for patient outreach and to update computer systems to handle reporting of illnesses and vaccinations.

“We do quite a bit of Covid testing, and then to add the vaccines, we really had to segregate staff — that’s costly, because the vaccinators for the most part are nurses,” said Paloma Izquierdo-Hernandez, Urban Health Plan’s president and CEO. “Not only is there a short supply of nurses, but they’re expensive.”

Izquierdo-Hernandez said scheduling second appointments for the two-dose vaccines and completing state-mandated paperwork add to the new workflow.

“So combining all of that and just trying to do the best job that we could — without additional funding — is very difficult,” she said.

El Centro de Corazón, Urban Health and 12 other clinics have paid for some of those costs with $50,000 grants apiece from a $1 million fund started by Hispanic Federation, a network of Latino-led and Latino-serving health and human services providers.

The federation has been providing money for food, housing and other assistance to its 300 member organizations from a $16 million fund.

“These are clinics that were telling us they needed money for staffing, more money to update their digital software — imagine you are going to get 900 doses of the vaccine. How do you operationalize that if you don’t even have the resources for that?” Miranda said.

Miranda testified last month before a congressional committee on inequities in vaccinations of Latinos and the need to increase the use of community clinics to reach more of the population.

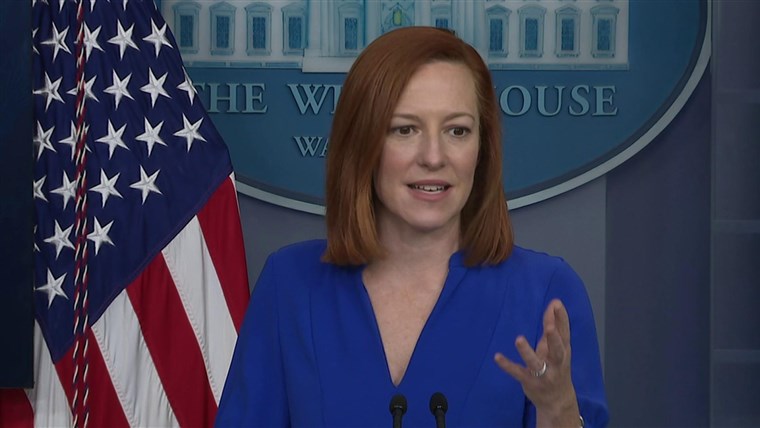

The previous administration chose to distribute through large hospital systems and thought offering vaccinations through pharmacies would be the magic bullet, Miranda said.

“We have seen that, so far, that is not necessarily the best way to help our community,” he said.

“Going to the local sports arena or larger health care systems, that is not easy for our population,” Young said. “Transportation is an issue. There are those that don’t have transportation to go through a drive-thru.”

In mid-February, the Biden administration announced a phased-in program of vaccinations at community health centers, sending vaccines directly to the centers.

The administration said more than 1,300 community health clinics serve almost 30 million people, about two-thirds of whom live at or below poverty level and 60 percent of whom who are members of racial and ethnic minority groups.

The $1.9 trillion Covid-19 relief package Biden signed Thursday includes funding that could help.

A plea for more vaccines

El Centro de Corazón, which has a patient population of about 13,000 people, got a supply of about 100 vaccine doses from the state in early January. It has received 975 more since, mostly in allocations of 100 or 200 doses, and has had few no-shows, she said.

“We were thankful for it — but by and large, we are not getting the levels we need to vaccinate our community,” said Marcie Mir, El Centro de Corazón’s CEO.

Jacob of Urban Health Plan also wants to see a steadier flow of vaccines. Right now, Urban Health Plan can book appointments only every two weeks because of the limited supply, he said.

Reports of vaccine hesitance across Latino communities have spread, but Jacob and Izquierdo-Hernandez said few patients refuse vaccinations.

However, Izquierdo-Hernandez said, many patients have benefited from consultations with one of Urban Health Plan’s doctors about the vaccines. As the vaccine supply improves, she hopes to expand the provider appointments to close the vaccination gap in the Latino community.

“Everyone has the responsibility of promoting vaccines. We always hear it from the government, which is part of the problem,” she said, “because some people are afraid of the government.”

Mir said another issue is those in the community who are unable to go to the clinics, so “we need to figure out how to go to them.” Setting up mobile clinics and going to people’s homes would help, she said.

Last month, Hispanic Federation’s Miranda asked the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis to send vaccination “strike teams” to places where hard-to-reach populations live and work.

He called for direct funding for partnerships with community-based organizations to create more vaccination sites, including mobile sites, as well as door-to-door outreach.

“Continuing to give low priority to Latinos and immigrants is not merely unfair; it is terrible public and economic policy,” Miranda said in a written copy of his remarks. “This country will not recover as quickly as it needs to if Latinos and immigrants continue to be treated as disposable, made invisible in policy discussions, or are left behind in the life-saving race to provide vaccines.”

Follow NBC Latino on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Recent Comments