People who take popular drugs for weight loss, such as Ozempic or Wegovy, may be at an increased risk of severe stomach problems, research published Thursday in the Journal of the American Medical Association finds.

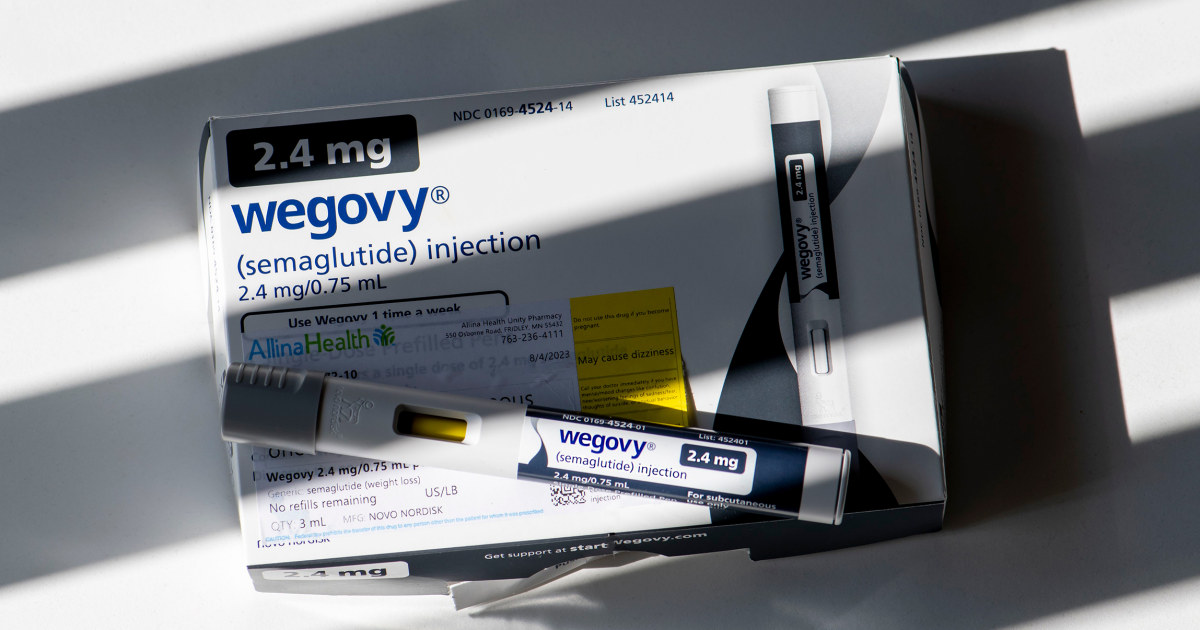

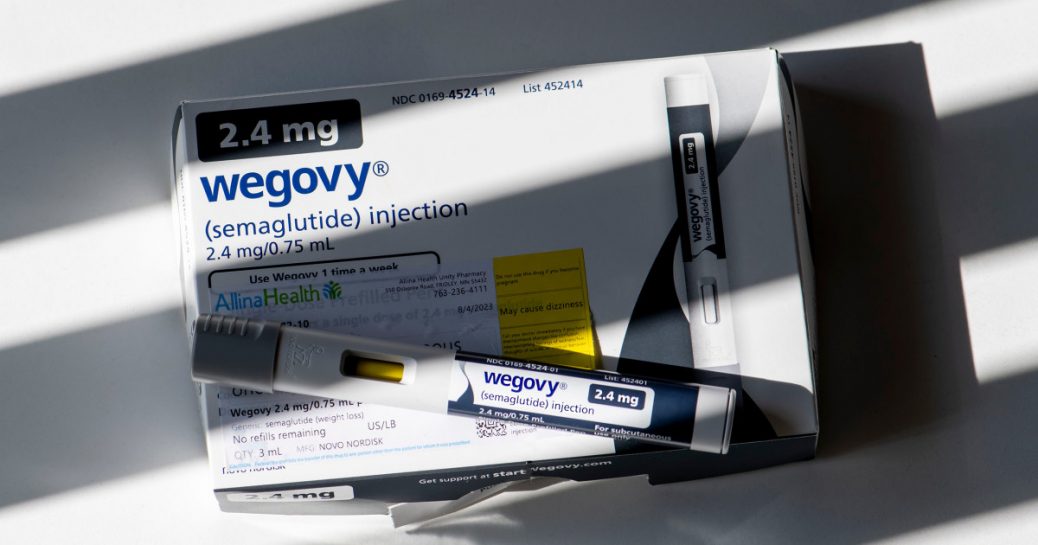

The brief report is the first study of its kind, the researchers say, to establish a link between the use of such drugs, called GLP-1 agonists, for weight loss and the risk of such gastrointestinal conditions. GLP-1 agonists include semaglutide — the drug found in Ozempic and Wegovy — and liraglutide, the drug used in Saxenda. Both drugs are made by Novo Nordisk.

“Although rare, the incidence of these adverse events can happen. I’ve seen it happen,” said lead author Mohit Sodhi, a medical student at the University of British Columbia Faculty of Medicine in Vancouver. “People should know what they’re getting into.”

The drugs were originally developed to help people with Type 2 diabetes manage their blood sugar levels but were later found to be effective for weight loss.

GLP-1 medications work, in part, by slowing down how quickly food passes through the stomach, leading people to feel fuller longer. But they can also lead to gastrointestinal side effects, including abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, as shown in clinical trials and noted on drug labels.

More recently, as the drugs have skyrocketed in popularity, there have been reports of patients who developed stomach paralysis, or gastroparesis. In August, Novo Nordisk was sued over claims that Ozempic caused a woman’s stomach paralysis. (Eli Lilly, which makes another GLP-1 drug, tirzepatide, was also included in the lawsuit.)

The new research, based on health insurance claims from 2006 to 2020 from more than 5,000 patients in the U.S., looked at how many people developed one of four serious gastrointestinal problems — biliary disease, gastroparesis, pancreatitis or bowel obstructions — after they were prescribed one of the weight loss drugs. About 4,100 of the patients were prescribed liraglutide, about 600 semaglutide and 650 the weight loss drug bupropion-naltrexone, which is not a GLP-1 medication.

Wegovy was not approved until 2021. However, Ozempic, which has the same active ingredient semaglutide, was approved in 2017 and some doctors prescribe it off-label for weight loss.

People included in the analysis all had records of obesity and did not have diabetes, which itself can cause gastroparesis.

Compared to people taking bupropion-naltrexone, people taking a GLP-1 drug had a higher risk of pancreatitis, bowel obstruction and gastroparesis, the study found. There was no increase in risk for biliary disease, which includes conditions that affect the gallbladder, the liver and the bile ducts, as its incidence was similar for both types of drugs.

Pancreatitis, or inflammation of the pancreatitis, occurred at a rate of about 5 cases per 1,000 users of semaglutide and 8 cases per 1,000 users of liraglutide. The condition causes severe abdominal pain and, in some cases, requires hospitalization and surgery.

Gastroparesis was seen at a rate of about 10 cases per 1,000 semaglutide users and 7 cases per 1,000 liraglutide users. The condition, which can be difficult to treat, causes severe nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain.

It can have “a significant impact on the quality of life,” Sodhi said.

Bowel obstructions — which occur when a blockage prevents food or liquid from moving through the intestines — were seen at a rate of 8 cases per 1,000 users of liraglutide. There were no observed cases in semaglutide users. Depending on the severity, surgery may be needed to treat a bowel obstruction.

Sodhi said that although the conditions are rare, the medications’ widespread popularity means that if 1 million people are prescribed those drugs, tens or even hundreds of thousands of people could experience them.

Read the latest on weight loss drugs

Allison Schneider, a spokesperson for Novo Nordisk, said in a statement that “patient safety is a top priority.” The product labels for Wegovy and Saxenda include information about potential side effects, including pancreatitis, acute gallbladder disease, ileus and delayed gastric emptying, she added. (Ileus refers to a type of bowel obstruction.)

“We work closely with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to continuously monitor the safety profile of our medicines,” Schneider said.

Dr. Andres Acosta, a gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic, said the findings tell us that GLP-1 medications are generally safe but may carry a risk of serious gastrointestinal side effects.

“I’ve been telling my patients all along that we need to understand that all medications, including GLP-1s, have potential risks,” said Acosta, who was not involved with the research. “And we know that the GLP-1 medications have a risk of nausea, vomiting and delay of gastric emptying.”

Still, Acosta was not overly swayed by the study’s findings, saying some of the side effects listed in it could be the result of patients’ rapid weight loss, not the medications. He said he would like to see a large randomized controlled clinical trial looking at people who received the medications or placebos. (The clinical trials that drug companies conducted prior to the drugs’ approval were not large enough to detect rarer side effects, Sodhi said.)

Dr. Shauna Levy, a specialist in obesity medicine and the medical director of the Tulane Bariatric Center in New Orleans, said she is unlikely to change her prescribing practices for GLP-1 medications after having reviewed the study’s findings.

“We still need to be careful,” Levy said. “This just further emphasizes, like many of things in the past, that these medications need to be regulated by a physician or a medical provider who is going to take a good history, monitor the patient closely and stop the medication if they have these side effects.”

She said the rare side effects do not scare her as much as the health conditions that come from obesity or being overweight.

“I can go into the hospital, have pancreatitis treated and stop taking the medication,” Levy said. “But if I die of a heart attack, no it doesn’t work.”

Dr. Susan Spratt, an endocrinologist and the senior medical director for the Population Health Management Office at Duke Health in North Carolina, advised that patients prescribed GLP-1 drugs should be counseled about starting the lowest dose and gradually increasing it, waiting at least four to six weeks before they escalate to the next dose.

Doctors should also discuss the risk of pancreatitis, which includes a history of gallstones or past cases of pancreatitis, and avoid its risk factors, which include drinking alcohol while using the medication.

Follow NBC HEALTH on Twitter & Facebook.

Recent Comments