Once it was logged by the MPC, it was Farnocchia’s job to try to plot out 2024 YR4’s possible paths through space, checking to see if any of them overlapped with our planet’s. He works at NASA’s Center for Near-Earth Object Studies (CNEOS) in California, where he’s partly responsible for keeping track of all the known asteroids and comets in the solar system. “We have 1.4 million objects to deal with,” he says, matter-of-factly.

In the past, astronomers would have had to stitch together multiple images of this asteroid and plot out its possible trajectories. Today, fortunately, Farnocchia has some help: He oversees the digital brain Sentry, an autonomous system he helped code. (Two other facilities in Italy perform similar work: the European Space Agency’s Near-Earth Object Coordination Centre, or NEOCC, and the privately owned Near-Earth Objects Dynamics Site, or NEODyS.)

To chart their courses, Sentry uses every new observation of every known asteroid or comet listed on the MPC to continuously refine the orbits of all those objects, using the immutable laws of gravity and the gravitational influences of any planets, moons, or other sizable asteroids they pass. A recent update to the software means that even the ever-so-gentle push afforded by sunlight is accounted for. That allows Sentry to confidently project the motions of all these objects at least a century into the future.

COURTESY PHOTO

Almost all newly discovered asteroids are quickly found to pose no impact risk. But those that stand even an infinitesimally small chance of smashing into our planet within the next 100 years are placed on the Sentry Risk List until additional observations can rule out those awful possibilities. Better safe than sorry.

In late December, with just a limited set of data, Sentry concluded that there was a non-negligible chance 2024 YR4 would strike Earth in 2032. Aegis, the equivalent software at Europe’s NEOCC site, agreed. No bother. More observations would very likely remove 2024 YR4 from the Risk List. Just another day at the office for Farnocchia.

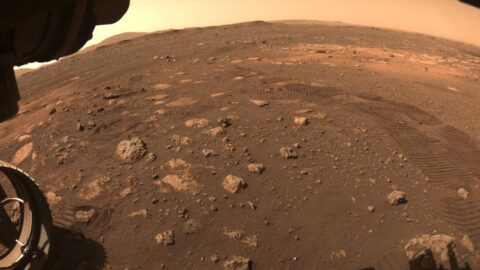

It’s worth noting that an asteroid heading toward Earth isn’t always a problem. Small rocks burn up in the planet’s atmosphere several times a day; you’ve probably seen one already this year, on a moonless night. But above a certain size, these rocks turn from innocuous shooting stars into nuclear-esque explosions.

Reflected starlight is great for initially spotting asteroids, but it’s a terrible way to determine how big they are. A large, dull rock reflects as much light as a bright, tiny rock, making them appear the same to many telescopes. And that’s a problem, considering that a rock around 30 feet long will explode loudly but inconsequentially in Earth’s atmosphere, while a 3,000-foot-long asteroid would slam into the ground and cause devastation on a global scale, imperiling all of civilization. Roughly speaking, if you double the size of an asteroid, it becomes eight times more energetic upon impact—so finding out the size of an Earthbound asteroid is of paramount importance.

In those first few hours after it was discovered, and before anyone knew how shiny or dull its surface was, 2024 YR4 was estimated by astronomers to be as small as 65 feet across or as large as 500 feet. An object of the former size would blow up in mid-air, shattering windows over many miles and likely injuring thousands of people. At the latter size it would vaporize the heart of any city it struck, turning solid rock and metal into liquid and vapor, while its blast wave would devastate the rest of it, killing hundreds of thousands or even millions in the process.

Recent Comments